Manufacturing Data Hub

This article explains the components of a Manufacturing Data Hub (MDH) and why the system must have these particular components to meet the needs of large, modern manufacturing environments.

In other words, this article explains why Rhize made the choices it did to become the world’s first manufacturing data hub. For introductory explanations about Rhize in particular, read What is Rhize? and How Rhize works.

What is an MDH?

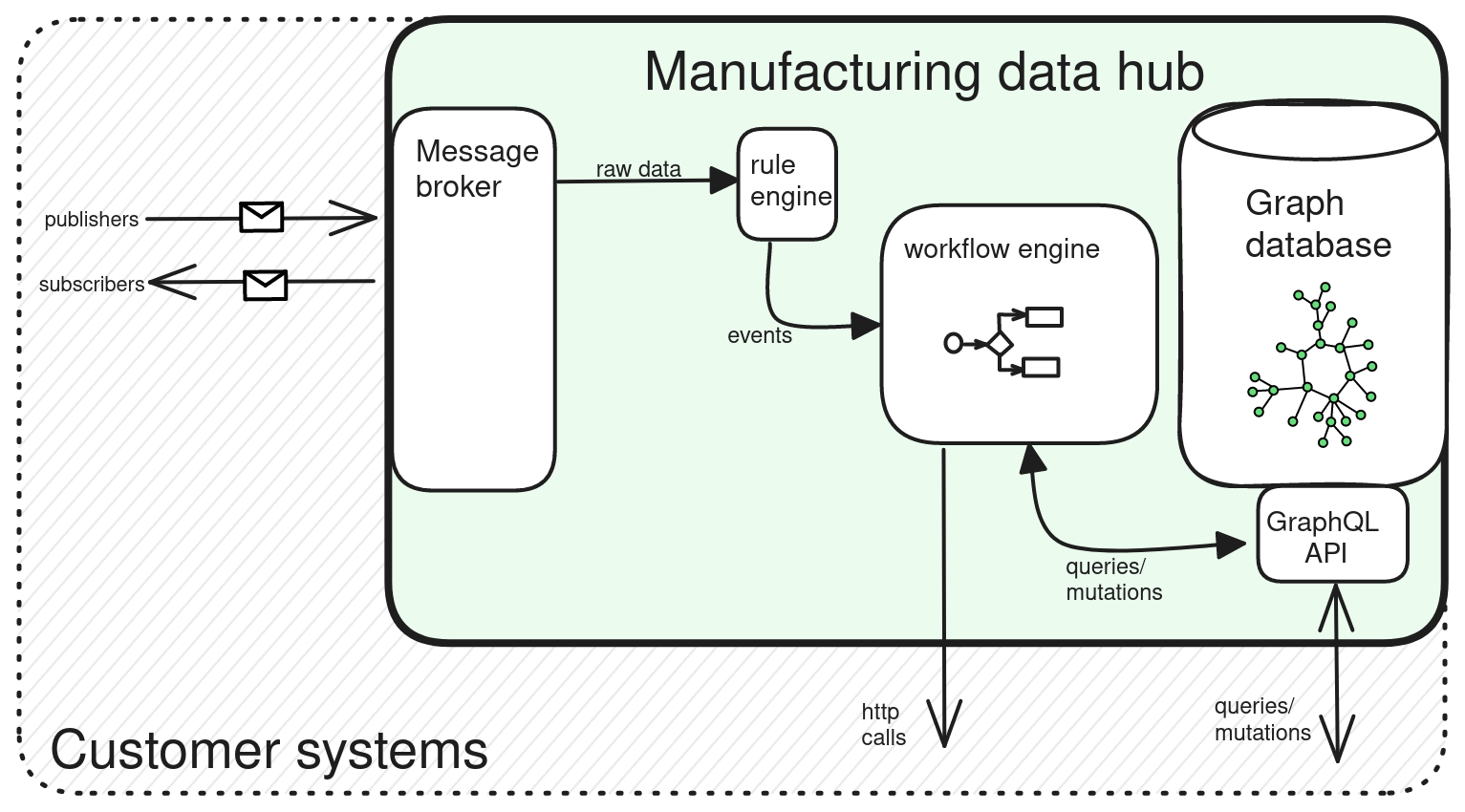

A manufacturing data hub is a system that collects all manufacturing events, stores them in a standard model, and has a programmable engine that runs user logic to receive, transform, and send messages across different devices in a manufacturing operation. Since it comes with all the necessary backend components—message handling, logic, and storage—an MDH also serves as a backend for manufacturers to build custom MES and MOM applications.

Components

An MDH is not just a storage or message system. It is a coherent system of interrelated parts and interfaces, whose components include:

- A high-performance graph database with a standardized schema

- A data model based on manufacturing standards

- An API to interact with the data

- An agent that listens for tag changes from data sources

- A rules engine that monitors tag changes and triggers user workflows when conditions are met

- A message broker that communicates events to and from various systems

- A workflow engine that processes, transforms, and contextualizes tag and event data

- The IT infrastructure that this all runs on, which at a certain scale must be clustered.

Technical requirements

Besides its components and features, Rhize is explicitly designed to meet the needs of manufacturing operations of any scale. This goal requires a high standard of operational performance, robustness, and extensibility:

- Zero Downtime Architecture. A data hub such as Rhize is used in mission-critical environments that run every hour of every day. Outages are unacceptable. Operators must be able to update every component of the system without taking it offline.

- Secure. Users must be able to securely access and integrate with the hub across applications in the enterprise. So the database requires native OAuth2 security integration for seamless single-sign-on.

- ACID-compliant. The critical features of an MES require the guarantee of an ACID database. Consistency and availability must be maintained even as the system scales horizontally.

- Headless operation. Users must be able to use the data hub as a backend to run MES functions, using frameworks or low-code tools to build any frontend on top of these functions. This flexibility is how the MDH can adapt to any manufacturing process: Rhize provides the means to store, standardize, and handle information flows; users build on top of this backend to create the applications, workflows, and interfaces that make sense for their use cases.

- Type-safe. Uncontrolled schemas in messages become brittle at scale. Unlike a pure MQTT architecture, which does not check the schema of message payloads, the MDH must enforce that data has a standard structure at the moment that the data is written to the database.

- Extensible but Standardized. While the data hub is built on the ISA-95 standard, it must be able to extend to include customer-specific schemas.

- Process orchestration. The hub must be able to coordinate tasks handled by multiple systems concurrently and provide a way for users to automate and combine workflows.

Why an MDH needs this design

Rhize chose its components deliberately, after careful consideration and years of real-world experience. The following sections describe how these components work together and how this design arose from the landscape of manufacturing automation.

Point-to-point reaches scaling issues

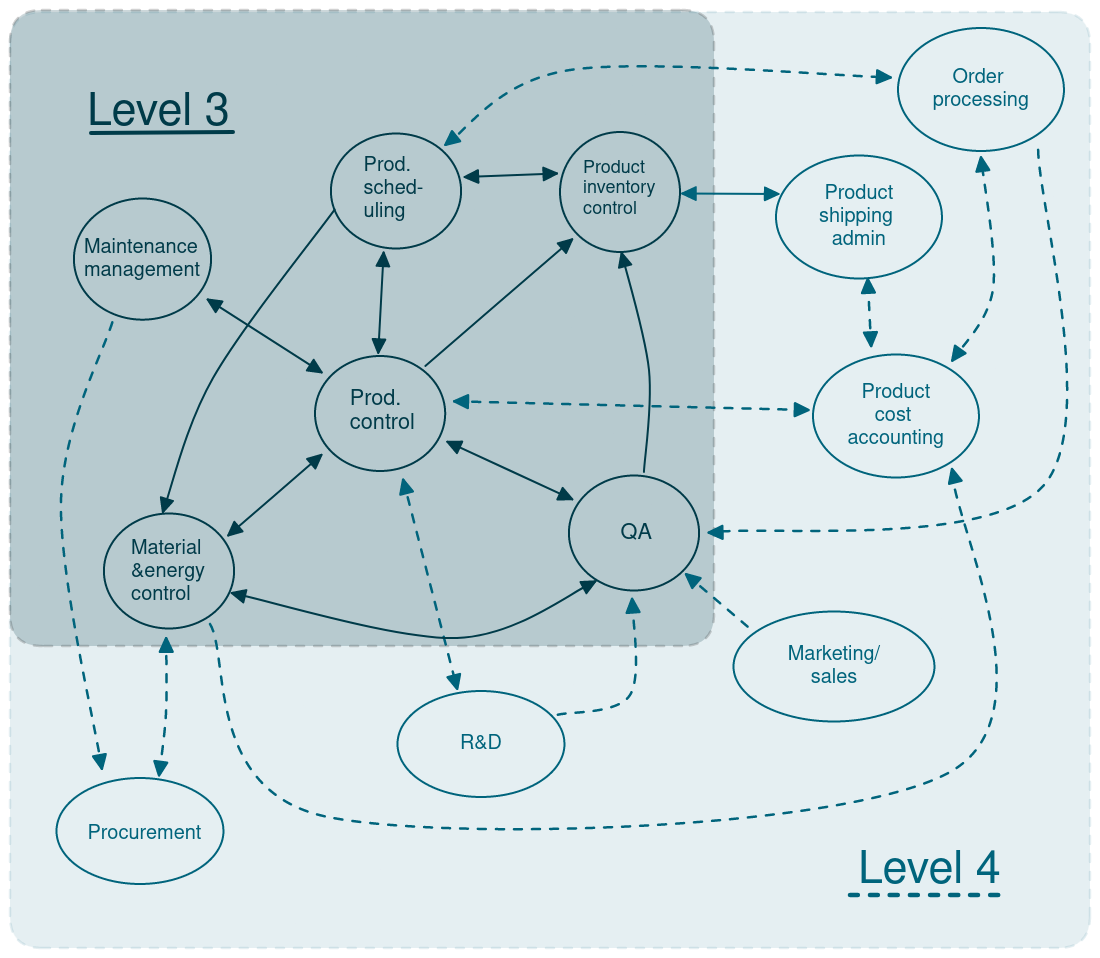

In early efforts to digitize manufacturing, information often flows from point to point. Each node in the system communicates directly with the other nodes that it sends data to or receives data from. While this form of communication is initially simple to implement, it also tightly couples services. As the system scales, the complexity of point-to-point communication increases non-linearly. With each node, the system becomes increasingly fragile and unobservable.

For example, notice how many channels of communication are maintained in this stylized diagram of information exchange between level-three and level-four systems in a point-to-point topology:

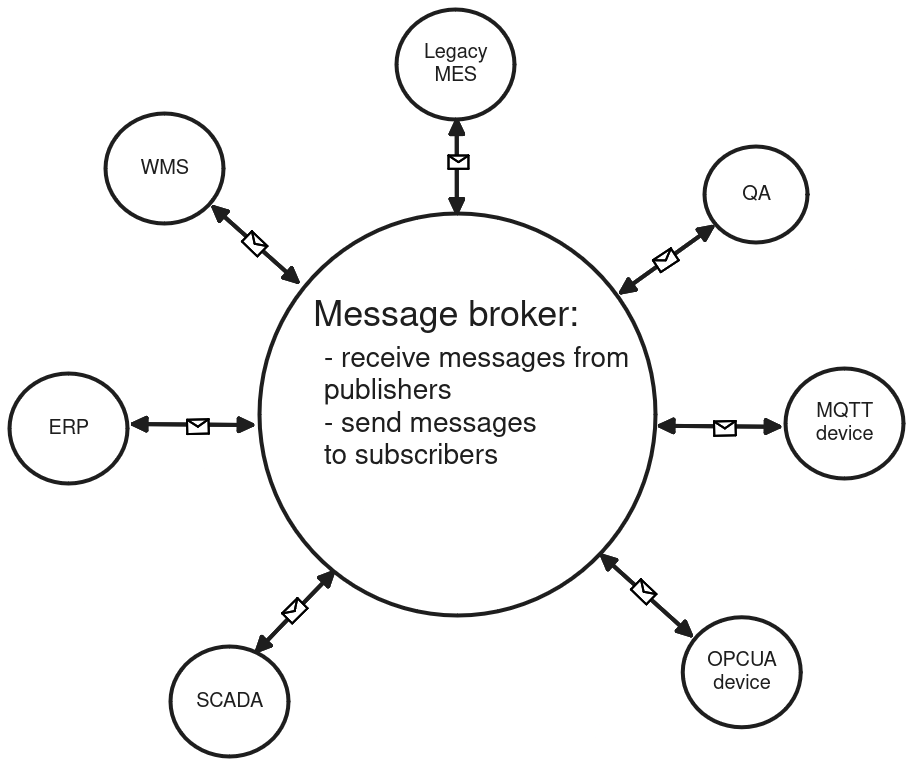

Pub/sub messaging decouples devices

When point-to-point communication becomes too difficult to maintain, the hub-and-spoke approach presents the logical next step. In this topology, a central hub coordinates communication between nodes.

Some systems achieve a hub and spoke through polling, where each device sends a request to the hub at some interval to check whether resources changed. However, considering the number of devices and volume of exchange in manufacturing, polling can create a massive amount of unnecessary traffic.

Instead of polling, the publish-subscribe pattern can be a more efficient way to decouple communication. Event producers publish topics to a message broker, and the message broker sends the event to consumers that subscribe to the particular topic. With the proliferation of IoT devices and the popularity of the MQTT protocol, publish-subscribe messaging has gained widespread adoption in manufacturing.

While publish-subscribe patterns resolve issues of coupled communication and data accessibility, they don’t address how to make this data useful:

- How can users collect and organize the data for analysis?

- How can this data drive further automation?

An operation with many data sources likely also has many different structures of its in-flight messages. The MQTT format, for example, has no prescribed payload format: structured JSON and binary blobs are equally valid. While such flexibility provides excellent convenience for producers, the lack of uniformity can make wider integration efforts convoluted and unmaintainable.

The philosophy of a data hub is to address these problems without comprising flexibility. So its central components, the database, schema, and message and event handlers, can integrate disparate systems while providing a common, standardized storage for the data exchanged between these systems.

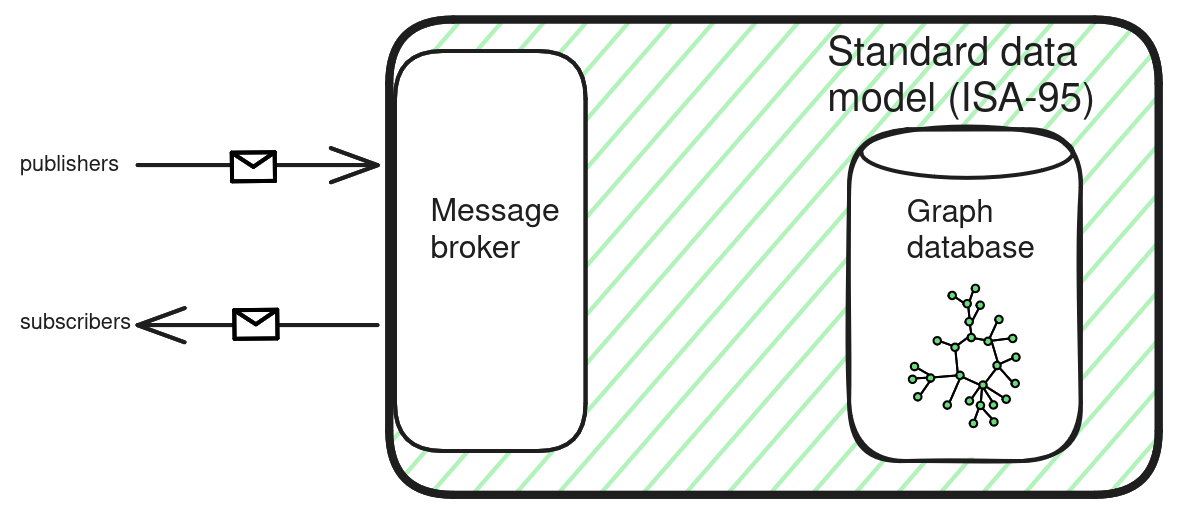

A standard graph model provides context

Every event, person, and object in a manufacturing system is inter-connected. To adequately process incoming event data, manufacturers need to contextualize it, where each event carries additional information about its context within the larger system. This context is framed by the information model that represents the system.

For a coherent model of the system, manufacturers need to be able to store assets and event data according to a standardized schema. To scale, this model needs to be suitably thorough and generic. For any organization, it would be an enormous undertaking to write a bespoke model. Fortunately, decades of collaboration have already generated a suitable standard: ISA-95.

The ISA-95 standard provides a comprehensive data model for manufacturing. As it happens, its object-oriented system of attributes and relations has an inherent graph structure. This harmony of ISA-95 and graph structures makes a graph database a perfect foundation for the manufacturing data hub:

- The schema provides the complete model, suitable to any scale

- The graph database provides the structure that coheres with the inter-related reality of manufacturing

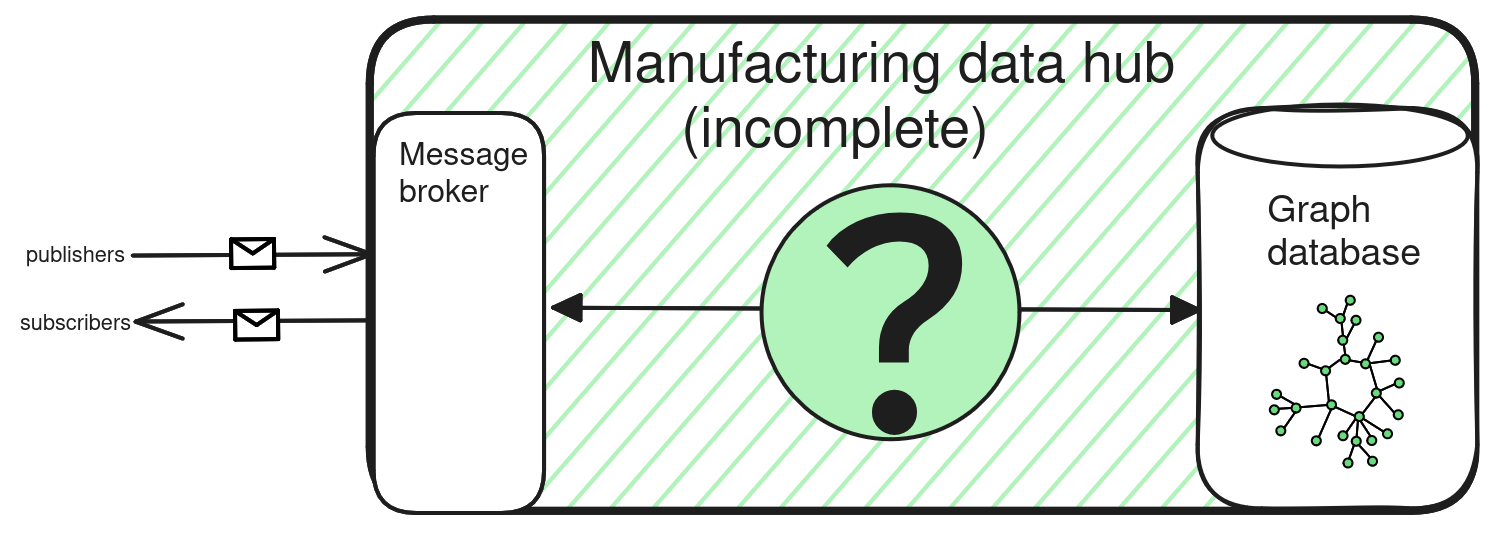

However, while publish-subscribe messaging decouples communication, and the ISA-95 database provides a sensible way to contextualize the messages of this data, the system still needs a bridge between the message stream and the long-term, standardized storage. This gap reveals missing components:

- The system needs to structure raw message data in its ISA-95 representation.

- Users need a way to access the database and message flow to program their own applications.

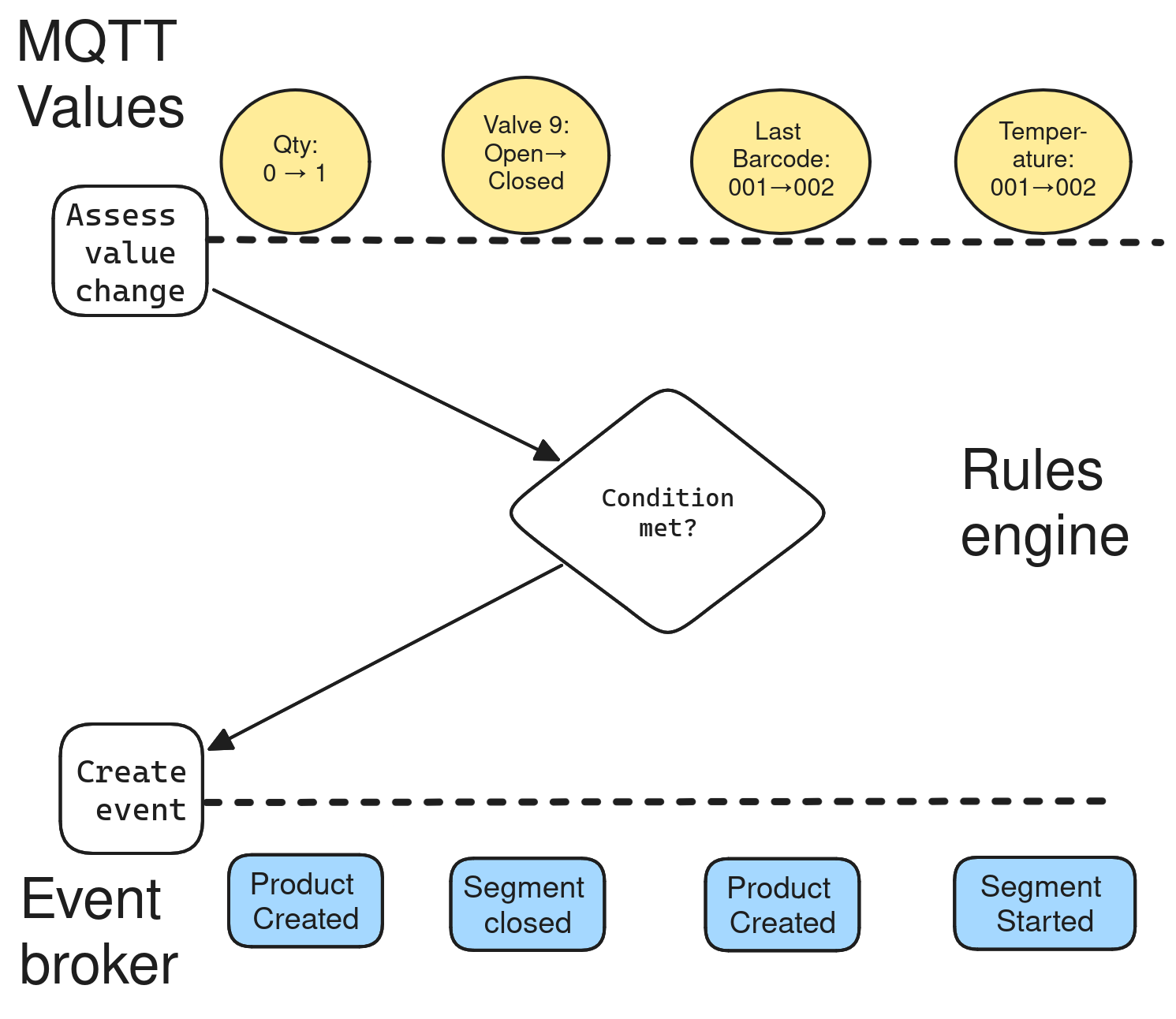

The rules engine creates events

After the hub receives a message, it must evaluate whether the data is significant enough to constitute an event. This is the function of the rules engine: it assesses message values for changes and then evaluates whether these values should be classified as significant events.

Once the system receives an event, users then need a way to be able to process it.

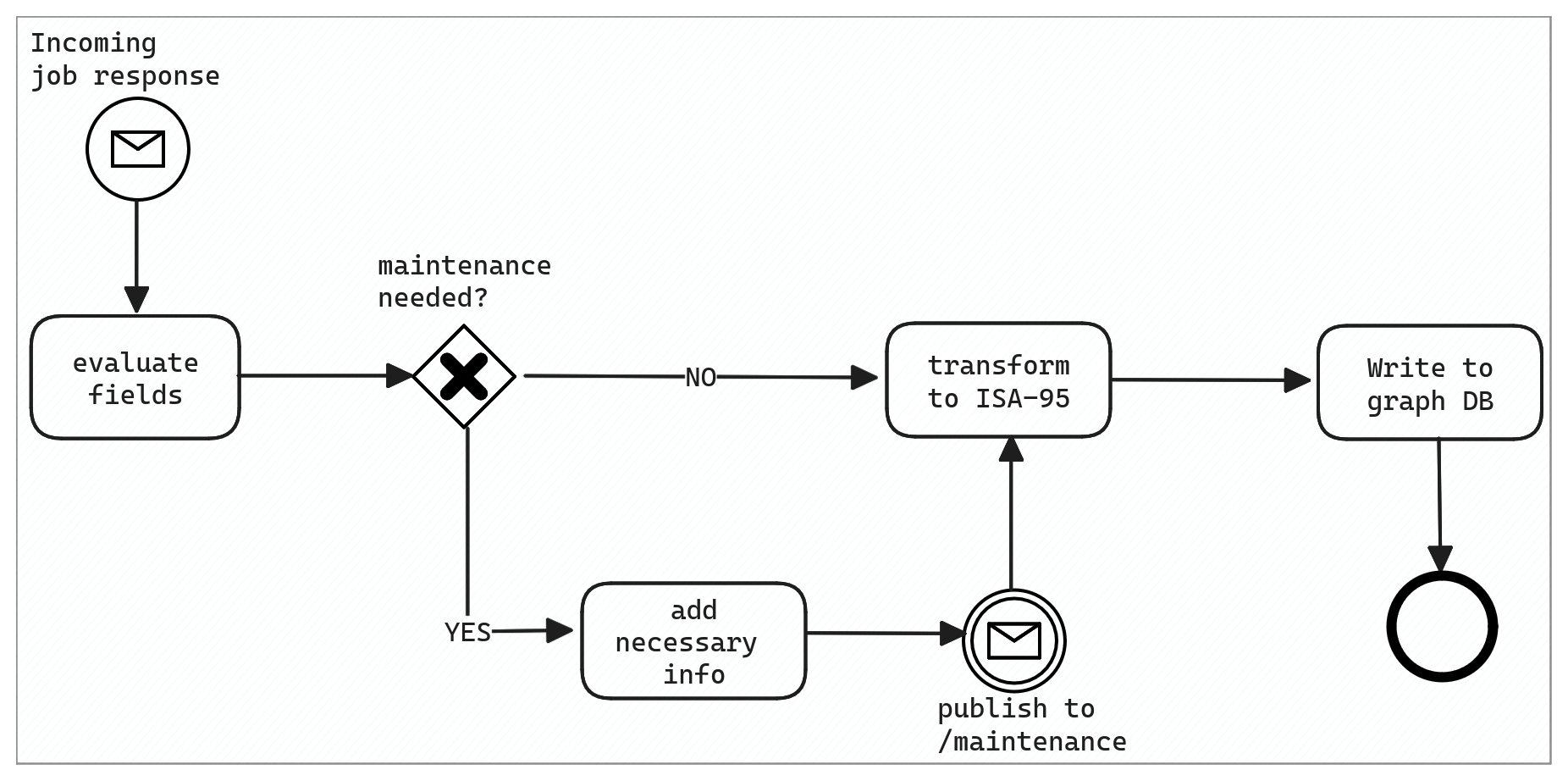

A workflow engine makes the system responsive

For true “ubiquitous automation” of manufacturing processes, an MDH must provide a way for users to write their own logic to handle events as they happen. Thus, the hub needs a workflow engine that can send messages, process data, and interact with the database in real-time.

The data hub also must be agnostic about the information it receives, so the event handler must have a way to transform incoming events and represent them in the database schema. Without such transformation, the burden of ISA-95 standardization falls on the event producer. This is both inconvenient for the user and more architecturally fragile: a second place where transformation can happen is also a second point of failure. As long as the producer and consumer can accept and receive the same encoding (for example, JSON), the data hub should be responsible for enforcing standardization.

With components for data ingestion, processing, and standardized storage, the MDH has all the necessary functionality to serve as a knowledge graph, MES backend, and integrator of legacy systems. However, this capability cannot be realized unless the system is usable for the widest range of people.

Sensible interfaces make it accessible

For many who work in industrial automation, IT is part of a job, not a job in itself. So, a well-designed manufacturing data hub should provide high-quality abstractions and interfaces that minimize the need for thinking about IT systems (instead of manufacturing ones).

GraphQL, with its single endpoint and precise controls, makes an ideal API interface for the MDH graph database. Queries resemble the structure of the data itself, requiring no recursive joins or intermediary object-relation models. GraphQL also pairs perfectly with a data model based on ISA-95, whose object model has a graph structure, itself a model of the interconnected reality of actual manufacturing.

While GraphQL provides the API to query and transform the data, it cannot execute logic. So, the rules engine should also provide a graphical interface to make event handling as accessible as possible.

However, one final piece is missing: the system must be robust enough for the data-intensive world of manufacturing IT.

Distributed execution provides robustness

The final factor is that the components of an MDH must run on distributed systems. Large manufacturing operations can generate enormous volumes of data. At some point, scaling vertically (with better hardware on single devices) is impossible. Besides size constraints, single devices also create single points of failure.

So, an MDH must scale horizontally, where different nodes share computation responsibilities, and extra volumes add data replication.

Read more

Our blog has some articles that define what a data hub is: